Science, Consciousness and the Brain

Course Materials

Course Outline

Science, Consciousness and the Brain continues our investigation into the question of what it means to be conscious in the light of the phenomenological philosophical investigations of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. Here we look in more detail at Husserl and Heidegger’s understandings of science and using this perspective consider our contemporary scientific understandings of consciousness. This questioning of science will include an examination of the development of the scientific worldview within which scientific conceptions of consciousness have been framed, and an examination of recently developed theories concerning the kinds of physical brain processes that could be associated with first-person conscious experience (looking particularly at predictive coding models). The final aim is to examine how such an objective, scientific understanding of consciousness can be related back to a phenomenological understanding of consciousness as it is revealed in immediate conscious experience.

Topic List

Topic One: Being-in-the-World and Being-in-a-Brain

Lecture Outline:

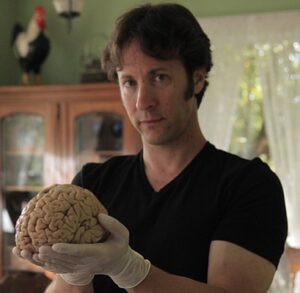

To get back into the space of phenomenology, this week we are going to revisit the final lecture of the 2018 offering of Introduction to Phenomenology: “Being-in-the-World and Being-in-a-Brain”. This lecture took a critical look at the “What is Reality?” episode of the BBC documentary “The Brain with David Eagleman” (Eagleman is the man holding the model brain in the photograph under the buttons).

Your task is to reconsider Eagleman’s question ‘What is Reality?’ in the light of his TV program and in the light of Heidegger’s “Blossoming Tree” reading (from What is Called Thinking) and my lecture notes (see this week’s course materials).

The questions we looked at last time were: What do you think Heidegger’s response to Eagleman’s position would be? For example, what does Heidegger have to say about science and reality in this week’s reading? And what about yourself? Do you agree with Eagleman’s view of consciousness? If so, does that mean you disagree with Heidegger? In what way exactly? Or in what way is Eagleman mistaken? Or is it possible to see them both as being correct each in their own way?

Lecture Recording: Part One:

Lecture Recording: Part Two:

Lecture Recording: Part Three:

Lecture Recording: Part Four:

Course Introduction

Being-in-the-World and Being-in-a-Brain

This is the first offering of Science, Consciousness and the Brain and after this week we will be covering entirely new material. It is open to all students who have completed Introduction to Phenomenology in previous years. This new course assumes that students already have familiarity with the material delivered in that earlier course. The course is also open to students who have not completed the introductory course, but are willing to catch up outside of classes on the introductory course material, including lecture recordings. This material is available on the Introduction to Phenomenology resources page.

What is the course about?

Science, Consciousness and the Brain continues our investigation into the question of what it means to be conscious in the light of the phenomenological philosophical investigations of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. Here we look in more detail at Husserl and Heidegger’s understandings of science and using this perspective consider our contemporary scientific understandings of consciousness. This questioning of science will include an examination of the development of the scientific worldview within which scientific conceptions of consciousness have been framed, and an examination of recently developed theories concerning the kinds of physical brain processes that could be associated with first-person conscious experience (looking particularly at predictive coding models). The final aim is to examine how such an objective, scientific understanding of consciousness can be related back to a phenomenological understanding of consciousness as it is revealed in immediate conscious experience.

This week’s material

To get everyone back into the space of phenomenology, this week we are going to revisit the final lecture of the 2018 offering of Introduction to Phenomenology: “Being-in-the-world and Being-in-a-brain”. This lecture took a critical look at the “What is Reality?” episode of the BBC documentary “The Brain with David Eagleman”. This program is still available on youtube via this link. Your task is to reconsider Eagleman’s question ‘What is Reality?’ in the light of his TV program and in the light of Heidegger’s “Blossoming Tree” reading and my lecture notes (see the attachments below). The questions we looked at last time were: What do you think Heidegger’s response to Eagleman’s position would be? For example, what does Heidegger have to say about science and reality in this week’s reading? And what about yourself? Do you agree with Eagleman’s view of consciousness? If so, does that mean you disagree with Heidegger? In what way exactly? Or in what way is Eagleman mistaken? Or is it possible to see them both as being correct each in their own way?

Science Topic 1 Overheads

Eagleman Transcript

Heidegger Blossoming Tree Reading

Topic Two: The Mathematization of Nature

Lecture Outline:

This week we will be looking in detail at Section 9 of Husserl’s Crisis of European Sciences entitled ‘Galileo’s Mathematization of Nature’. This reading expresses Husserl’s understanding of the origins of modern science in the physics of Galileo.

Your task is to carefully read §9 and §10 of the Crisis (see this week’s reading) and to come to class with any questions or difficulties you may have encountered. It is not an easy read, but I believe it is worth the effort to understandingly grasp what is being said – it certainly was for me – and hopefully I will be able to get this across in the next class.

Note: Part Two of the lecture recording went missing on my phone and I fear it is now lost forever.

Lecture Recording: Part One:

Science Topic 2 Overheads

Husserl Crisis Reading

Topic Three: Heidegger on Modern Science and Mathematics

Lecture Outline:

In Topic Three we will be looking at Heidegger’s understanding of the mathematical essence of modern science. This will involve a detailed consideration of the Modern Science, Metaphysics and Mathematics section of his book What is a Thing? (which was also published as a Chapter in Heidegger’s Basic Writings, see this week’s reading).

The reading continues our consideration of the mathematical foundations of modern science that we started in Topic Two with Husserl’s investigation of Galilean Science and the mathematization of nature. Here Heidegger takes a different approach to Husserl but one that complements rather than contradicts what Husserl has to say.

I think you will find this Heidegger selection easier to read than Husserl, but maybe not so easy to understand. The central question is, what does Heidegger mean by ‘the mathematical’? As is usual in these later writings, Heidegger pursues this question by going back to the Greeks. Let us see if we can follow him…

Lecture Recording: Part One:

Lecture Recording: Part Two:

Science Topic 3 Overheads

Heidegger Science Reading

Topic Four: Hans Jonas on Darwinism

Lecture Outline:

In Topic Four I shall first need to finish last week’s lecture and look at Heidegger’s analysis of Descartes’ project of providing a metaphysical foundation for modern science. After that we will take a break from our famous duo of Husserl and Heidegger, and look at the philosophical biology of Hans Jonas.

Jonas was a student of Heidegger’s who later came to reject what he understood as Heidegger’s existentialism. In this week’s reading (Jonas’ Philosophical Aspects of Darwinism) we shall continue our investigation into how modern science has structured contemporary understandings of what is and what is not considered to be real. Here we look at the effect of Darwin’s theory of evolution on our conception of what it means for something to be alive in a material universe.

Lecture Recording: Part One:

Lecture Recording: Part Two:

Science Topic 4 Overheads

Hans Jonas Darwinism Reading

Topic Five: Hans Jonas on Life and Metabolism

Lecture Outline:

Last week (in Topic Four) we only just started the Hans Jonas reading on Darwinism, so I anticipate we will spend most of this week’s class finishing that material.

However I am giving you another Jonas essay for Topic Five that I would like you to read before class (see this week’s reading). This essay goes beyond the historical considerations of the readings up to now, and looks into the question of what it means for something (someone) to be alive. This question is central for the rest of the course, so it will be good to start our inquiry as soon as possible, as it is going to require some serious consideration…

Lecture Recording: Part One:

Lecture Recording: Part Two:

Science Topic 5 Overheads

Hans Jonas Metabolism Reading

Topic Six: Autopoiesis

Lecture Outline:

As predicted we did not get to the Jonas reading from Topic Five so we will now be covering it in Topic Six. If you haven’t read it yet then you can download it from Topic Five.

Given we have an extra week I am giving you another reading that will help clarify the point Jonas is making about the special nature of the process of metabolism and how it distinguishes living beings from inanimate matter. Jonas was a trailblazer in this area and it is only now that the ideas he was proposing are being taken seriously in mainstream thinking – although the connection back to Jonas is generally not acknowledged – instead the debate is centred on the concept of autopoiesis, as proposed by Maturana and Varela back in 1973. They provided a more formal and biological notion of that form of organisation that distinguishes the animate from the inanimate.

Although I generally give you the original texts, in this case I think a more non-technical account of autopoiesis is needed, given that we are studying philosophy and not biology. Therefore I have chosen the What is Life

Note: The lecture overheads are available above in Topic Five.

Lecture Recording: Part One:

Lecture Recording: Part Two:

Capra & Luisi Autopoiesis Reading

Topic Seven: Heidegger on Organism

Lecture Outline:

Following on from the end of last week’s lecture we were talking of the distinction between animal being and human being. There was mention of language and of image making. Hans Jonas has another essay on image making but given the general feedback I decided to return to Heidegger and investigate what he has to say concerning what it means to be alive and the distinction between animal being and human being.

I have therefore given you a rather large section (50 pages, see this week’s reading) from the Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics lecture series where Heidegger attempts to uncover the essence of what it means to be an organism. Part of his aim here is to illuminate what it means to be ‘world-forming’ (which he takes to be essential to our being human) by negatively showing that the animal does not have world.

It’s another challenging read – and you should probably start this sooner rather than later.

Lecture Recording: Part One:

Lecture Recording: Part Two:

Science Topic 7 Overheads

Heidegger Organism Reading

Topic Eight: Metzinger's Ego Tunnel

Lecture Outline:

The subtitle for the course is Science, Consciousness and the Brain. So far we have looked into the history of science and how it has structured our understanding of what it means to be alive and conscious from the perspective of the phenomenology of the early to mid 20th century. But (except for David Eagleman’s documentary) we have not explicitly considered the understanding that contemporary science has reached concerning our being the beings that we are.

The inevitably leads us into neuroscience, cognitive science and contemporary philosophy of mind – as it is taught and practiced at (for example) the University of Sussex. As you will discover, the perspective of modern cognitive science presents a picture of conscious experience that is fundamentally opposed to the approach we have been taking up until now. To give you an idea of this, I have chosen the introduction and first two chapters of Thomas Metzinger’s book The Ego Tunnel as this week’s reading.

The Ego Tunnel is intended for a non-philosophical audience, so attempts to explain the issues without assuming too much background. Your task is to read this material on two levels:

Firstly the text is genuinely informing about the scientific advances that have been made in understanding the relationship between consciousness and the brain, so should be read as a source of new information.

Secondly, and more importantly, I would like you to read Metzinger critically: we have been looking in detail at how the presuppositions of materialistic science have caused us to overlook the immediate significance of our being conscious and what that means. And yet here is a leading contemporary philosopher, fully immersed in the materialistic (so-called naturalistic) scientific tradition, who talks of little else but consciousness. So in what way is Metzinger ‘overlooking’ what it means to be conscious? Or perhaps you think he is not overlooking consciousness at all. Either way I’d like you to treat the reading as a challenge to what we have been accepting up to now, and as something to stimulate some independent thought on your part as to the meaning of what we are doing in this course.

Finally, to get an idea of how Heidegger would have responded to Metzinger I have included an excerpt from History of the Concept of Time dealing with perception and representation (see this week’s Heidegger reading). Can you see how this reading undermines Metzinger’s notion of an Ego Tunnel?

Lecture Recording: Part One:

Lecture Recording: Part Two:

Science Topic 8 Overheads

Metzinger Ego Tunnel Reading

Heidegger Picture Thing Reading

Topic Nine: Heidegger, Cybernetics and the End of Philosophy

Lecture Outline:

Unsurprisingly we did not get to the end of Metzinger’s Ego Tunnel Lecture (Topic Eight) so this week I shall round up what we were saying about our contemporary scientific understandings of the relation between the brain and consciousness.

To this end I am including a paper from Andy Clark that gives a recent account of the predictive processing model of brain function mentioned in the Topic Eight lecture (see this week’s Clark reading). This model has its roots in cybernetics and the development of systems thinking and so brings us more or less up to date with what Heidegger would have called a cybernetic account of human intelligence. I do not plan to consider this paper in detail during the lecture – it is there mainly for the interest of those of you who want to inquire further.

I mention cybernetics because it is relevant to this week’s main reading: Heidegger’s The End of Philosophy and the Task of Thinking (see this week’s Heidegger reading). Here we reach Heidegger’s later thought on the situation in which we find ourselves – what he considers as the end of philosophy in the triumph of the scientific-technological world. I think this reading serves to complete the arc of course and I do not anticipate another reading next week – rather I plan to spend two weeks contemplating this material and also thinking about the assignment (see Assignment Specifications in Topic 10).

Lecture Recording: Part One:

Lecture Recording: Part Two:

Science Topic 9 Overheads

Heidegger End of Philosophy Reading

Andy Clark Predictive Processing Reading

Topic Ten: Heidegger and the Task of Thinking

Lecture Outline:

This is the final week of the course so there will be no new material, we just going to finish last week’s reading: Heidegger’s The End of Philosophy and the Task of Thinking.

We have already covered the End of Philosophy so now we only have to consider the Task of Thinking. This comprises the material from page 436 onwards of the Topic 9 reading. The lecture slides are also from Topic 9 (slide 7 onwards).

Lecture Recording: Part One:

Lecture Recording: Part Two:

Science, Consciousness and the Brain Assignment

Final Essay

Word Count: Minimum 3000 words

First Draft Due Date: 1st May 2019

Final Essay Due Date: 1st June 2019

(Both deadlines must be met in order to pass the assignment)

Select one of the course readings from the list below and explain in at least 3000 words how the matter that is introduced in the reading is relevant to the times in which we live now. I am looking for your own understanding here, but I am also expecting you to consider what other people have written and thought about your chosen piece. This means doing research on your own. You can quote from the lecture recordings but you should include evidence of the influence of these ideas beyond the lecture material, for example, on other living philosophers, writers, thinkers, scientists, in the media (documentaries, film, TV, radio, internet, etc.), in political discourse, in shaping world events, and so on. Note again: I am looking for an expression of your personal understanding not just a paraphrasing of what others have said (including me).

The Husserl reading from Topic Two (pp. 23-61 of The Crisis of the European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology)

The Heidegger reading from Topic Three (the Modern Science and Metaphysics Essay, published both in the Basic Writings anthology and What is a Thing

?) The Hans Jonas reading from Topic Four (Philosophical Aspects of Darwinism Essay, pp. 38-63 from The Phenomenon of Life).

The Hans Jonas reading from Topic Five (Is God a Mathematician

? Essay, pp. 64-98 from The Phenomenon of Life). The Heidegger reading from Topic Seven (pp. 212-261 from Martin Heidegger’s Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics Lecture series).

The Heidegger reading from Topic Nine (The End of Philosophy and the Task of Thinking Essay pp. 431-449 from the Basic Writings anthology).